In between posting ‘A bit more background, SMART goals and small victories’ and ‘Attentional strategies and entering flow on the final long run before the Anglesey Half Marathon’, my training had not gone exactly to plan.

While the rest of the group seemed to be hitting milestones, the only thing I seemed to be hitting was a brick wall. Within the space of well over a week, I’d not managed to get out for a run due to horrendous cramps that had me doubled over in pain for hours on end (a slight exaggeration, but you get the point!).

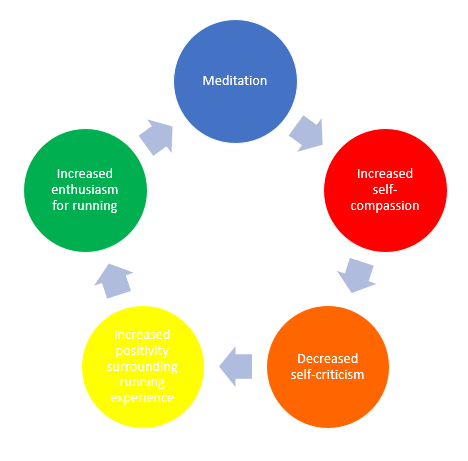

I took some time to reflect on the things I had achieved in that time, and I decided that dwelling on the negative was not the best way to move forward. Following a lecture with Dr Rhi Willmot, I knew that I had to start thinking about establishing new habits that would make getting out for a run a little easier.

Lally and Gardner (2013) define habits as ‘automatic behavioural responses to environmental cues’ that develop through repeating a certain behaviour within a certain context. Put more simply, habits are a result of routine behaviours that follow cues and result in rewards. The use of rewards is essential to habit formation, as they act as positive reinforcers which increase the likelihood of a behaviour being repeated.

According to many sources, forming a new habit takes approximately three weeks, or 21 days, to establish a habit (Dean, 2013) – seems easy enough!

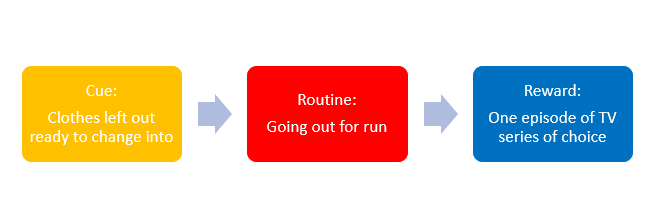

A habit can be broken down into three separate parts: cue, routine and reward. The cue is the stimulus that pre-empts the routine behaviour, which is the habit itself. The routine behaviour is then followed up immediately by a reward, which reinforces the routine behaviour and increases the likelihood of repetition (Judah, Gardner & Aunger, 2013).

At this point in time, I was still trying to get into the habit of going for a run. I had to establish what would work as a cue that would get me out for my runs, and then ensure that I had a nice reward to look forward to when I got back from my run.

The cue for me to go for a run was simple: I would leave my running gear out on a chair in my room the night before so it was all ready for me to change into in the morning. The routine would follow: I’d go out for my run. As soon as I got back home, I would reward myself by watching an episode of a TV show (and at the time, it happened to be Game of Thrones!).

While the cue-routine-reward structure provides a relatively simple framework for habit formation, its implementation requires a substantial amount of self-efficacy and motivation, which at the time, I did not seem to have.

Self-efficacy was first introduced by Bandura (1982), who defined it as one’s belief or judgement of one’s ability to complete a certain task.

In the initial weeks of training for the marathon, my running was not progressing as smoothly as I wanted it to and this was possibly due to the fact that I did not hold the same belief I could run several miles that I do now. A lot of the time, I would fall at the first hurdle of actually getting out the door. I didn’t enjoy running as there was very little that seemed enjoyable about it, meaning that there I didn’t have any reinforcers for actually going out for a run. Consequently, I had very little motivation to go out running.

Although the running itself can still be quite painful and difficult at times for me, when I get back after a run, I tend to experience that wonderful ‘post-run high’ resulting from the surge of serotonin that comes after doing exercise (Chaouloff, 1989). This in itself has become rewarding for me and has been beneficial in increasing my self-efficacy towards running.

However, Stanovich and West’s (2000) Dual Process Theory offers one possible explanation as to why I might have been more inclined to stay inside and less inclined to go for a run.

Their theory posits that any thoughts that arise can be processed by one of two systems. The ‘hot’ system (System 1) is described as being inflexible, automatic and requiring very little brain power meaning it often deals with more unconscious notions. The ‘cold’ system (System 2) is described as being more rule-based, analytical and requiring a greater amount of brain power, meaning it deals with more conscious notions.

So, when I’ve thought about going for a run, there has been a battle between the two systems in my mind, and throughout the past week it is clear that the ‘hot’ system has prevailed over the ‘cold’ system.

Staying inside has provided me with the instant gratification on which the ‘hot’ system thrives; the positive feeling generated by warmth, pain relief and food (and binge-watching Game of Thrones…eeek!) which has triumphed over the weaker ‘cold’ system that has urged delay of the gratifying positive feelings until I have completed a run.

Had I not been suffering with cramps, there may have been a slightly increased likelihood of the ‘cold’ system beating the ‘hot’ system.

Receiving positive encouragement and hearing reassuring information from others on the module about their own running struggles helped put my own into perspective. The positive encouragement has become a form of reinforcement that has spurred me on to going out running more, and this has, in turn, resulted in increased use of the ‘cold’ system.

“Motivation is what gets you started. Habit is what keeps you going.”

Jim Ryun

References

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122.

Chaouloff, F. (1989). Physical exercise and brain monoamines: a review. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 137(1), 1-13. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08715.x

Dean, J. (2013). Making habits, breaking habits. Oneworld Publications.

Judah, G., Gardner, B., & Aunger, R. (2013). Forming a flossing habit: An exploratory study of the psychological determinants of habit formation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18(2), 338-353. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02086.x

Lally, P., & Gardner, B. (2013). Promoting habit formation. Health Psychology Review, 7(1), S137-S158. doi:10.1080/17437199.2011.603640

Stanovich, K., & West, R. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 23(5), 645-726. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00003435