Unless you have been living under a rock for the past few weeks, you are probably aware that we are currently in the midst of a global pandemic: Covid-19, or Coronavirus as it is also known.

This has undoubtedly caused a great deal of disruption all over the world, but for me it has resulted in the postponement of both my upcoming running events (Liverpool RnR Marathon: 24/25th Oct; Reading Half Marathon: 1st Nov).

As a result of the rescheduling of these events, both of which I was really looking forward to given my recent positive experience at the Anglesey Half Marathon, I regret to say that my motivation to get out and run has declined massively. Prematurely moving back home, due to the suspension of all face-to-face teaching till the end of my degree, has left me feeling very demotivated to do virtually anything, including getting out for runs.

While I know that getting into some sort of routine in times of uncertainty is likely to have a positive effect on one’s well-being (Ludwig, 1997), I have found it extremely difficult to do so.

As the above demonstrates, I have always been hard on myself. Whilst I always try and come across as a person who is accepting of their faults and failures, I am a perfectionist at heart and with that comes the *toxic* trait of being very self-critical.

I know that I am not alone in this; according to research by Taranis and Meyer (2010), female athletes with high self-criticism were more likely to be perfectionistic in their personal standards. However, Taranis and Meyer’s (2010) research also revealed that those athletes who were highly self-critical also felt more compelled to exercise, which applies to me somewhat, as when I criticize myself, I sometimes do feel the urge to get out for a run more than when I am perhaps not so self-critical. This would suggest that a certain amount of self-criticism is a good thing!

Self-criticism is a negative evaluation of oneself (Gilbert, Clarke, Hempel, Miles & Irons, 2004), whereas self-compassion is an individual’s feelings of love, kindness and understanding that they would typically show to others towards themselves (Barnard and Curry, 2011). It has been found that increased self-compassion can reduce self-criticism, as shown amongst a group of female varsity athletes (Mosewich, Crocker, Kowalski and DeLongis, 2013).

Upon reflection of my feelings towards myself and my running over the past few weeks, it is clear that I am very self-critical whilst I am actually out running. I recently ran a distance of 5K after taking a bit of time off from running. My self-critical feelings towards my lack of exercise at the time were partly responsible for making me get out for the run – ‘good’ self-criticism; but while I was out running I continued to be very self-critical about the speed at which I was running and how difficult I was finding it – ‘bad’ self-criticism.

My brain kept telling me, “you should find this easy, you just ran the Anglesey Half Marathon for god’s sake!”, neglecting the fact that I’d not been out for a run in weeks and, as a result of not being particularly active, my stamina would’ve naturally decreased.

Being so critical of myself is something I very much want to change, and I will attempt to do this by increasing my self-compassion.

One way I will achieve this is by incorporating meditation into my daily routine. A study by Albertson, Neff and Dill-Shackleford (2014) found that a 3-week meditation intervention was highly beneficial in reducing body dissatisfaction and increasing self-compassion and body appreciation within a group of women.

The intervention in Albertson, Neff and Dill-Shackleford’s (2014) study was delivered as three different 20-minute podcasts that participants were instructed to listen to once a day for a week. Each week focused on a different aspect of self-compassion, starting with compassion itself, followed by affection and ending with kindness.

The authors of the study *very kindly* included a link to the website where these podcasts can be found so I will, in a sense, attempt to replicate the study by listening to the podcasts used within it (and I’ve included the link in case you want to have a go too!).

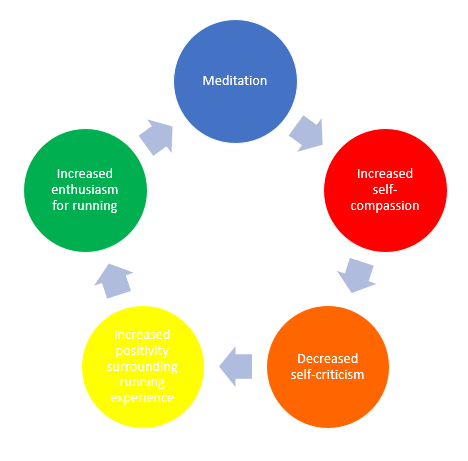

Meditation will be beneficial as it will help me increase my self-compassion which will decrease how much I criticize myself. This will, in turn, help me develop a more positive and reflective mindset making the experience of running more enjoyable for me, and will result in me feeling more enthusiastic about going for a run. In general, when I am in a positive mood I tend to be much more productive and willing to get out and do things that I find challenging, like running. Therefore, meditation will likely help me maintain a sense of positivity for a longer period of time and this will increase my enthusiasm to keep pursuing it.

Additional research by Neff, Kilpatrick and Rude (2006) across two separate studies demonstrated that self-compassion was useful in terms of reducing anxiety in the face of ego threats and that increased feelings of self-compassion were positively associated with increased wellbeing over a 1-month period.

Therefore, being self-compassionate is incredibly important to me if I am intent on keeping up with my running and increasing my general wellbeing – which I am!

A little over a month ago, PM Boris Johnson announced a nationwide lockdown, with the hopes of limiting the spread of the virus. Everyone was told to stay at home, only being allowed to leave for work if it was absolutely essential. The government also permitted people to leave their homes for one hour a day for exercise purposes, but they must do this either alone or with other people that they live with.

With those restrictions in place, it was clear I wouldn’t be running a marathon anytime soon, but that was a good thing, apparently. According to an article by Jane McGuire I saw recently on Runner’s World, given the current situation, people shouldn’t be going out and running long distances, as it takes its toll on one’s immune system. (And now, more than ever, we need our immune systems to be working at their optimum!)

This is fairly common knowledge amongst runners, and several pieces of research have provided support for this claim. In their paper, Fitzgerald (1988) discussed how Olympic athletes who undergo rigorous training put themselves at a higher level of susceptibility to infection as they enter a state of immunodeficiency. Marathon running, and long-distance running in general are considered to be very rigorous forms of exercise (Williams, 2008), therefore this research is highly applicable to marathon/long-distance runners, like myself.

Now that the date for the marathon has been pushed back, it means that I have a lot more time to focus on breaking down the ultimate goal of running it into several smaller goals.

Since starting the module, one thing I have consistently wanted to improve is my pace/timing. I definitely don’t see myself becoming the next Russell Bentley anytime soon, however I would like to see a decrease in the time it takes me to run a certain distance, for example: 5K, as this is a very clear way of seeing the progress I make.

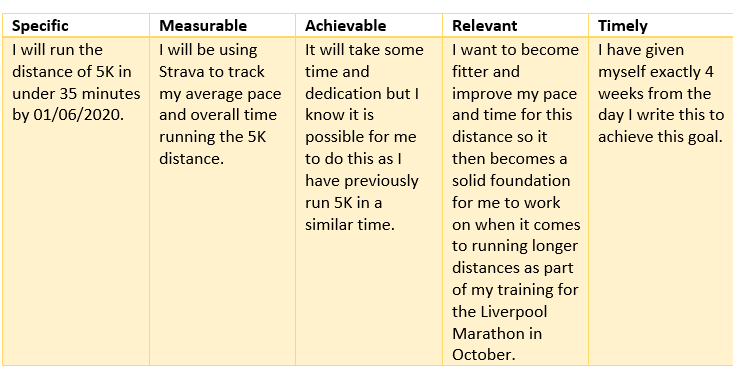

By working on more short-term goals, it makes the slightly larger long-term goals more easy to attain. As Bovend’Eerdt, Botell and Wade (2009) described in Step 3 of their flowchart for writing SMART goals, it is important to scale the initial goal, which in my case would be running the Liverpool Marathon, by adding sub-goals that are more easily achieved.

Of course, Bovend’Eerdt, Botell and Wade’s (2009) guide was designed for use within a clinical rehabilitation setting, however, having utilised the principles to generate my own SMART goals, I believe I have demonstrated that the basic principles are applicable to goal-setting of any kind.

So, for now, I am not going to be focusing on running long distances; my main goal over the next few weeks will be to work on getting my 5K time down. At the moment, it is around the 40-minute mark, but my PR (according to Strava) is roughly 37 minutes.

I think this calls for yet another SMART goal:

While I have been unable to achieve my previous SMART goal of running the Reading Half Marathon in under 3 hours, the new goal I have set myself will be of great benefit when I eventually come to running 13.1 miles in the future.

The last couple of weeks have been difficult for me, to say the least, but I am determined to get back to my running now that I have a more positive outlook to work on implementing, and a more achievable short-term goal to work on for the time being.

“You are never too old to set another goal or to dream a new dream.”

C. S. Lewis

References

Albertson, E., Neff, K., & Dill-Shackleford, K. (2014). Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: A randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness, 6, 444-454. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0277-3

Barnard, L., & Curry, J. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 289-303. doi:10.1037/a0025754

Bovend’Eerdt, T., Botell, R., & Wade, D. (2009). Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 352-361. doi:10.1177/0269215508101741

Fitzgerald, L. (1988). Exercise and the immune system. Immunology Today, 9(11), 337-339. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(88)91332-1

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring onself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 31-50. doi:10.1348/014466504772812959

Ludwig, F. (1997). How routine facilitates wellbeing in older women. Occupational Therapy International, 4(3), 215-230. doi:10.1002/oti.57

Mosewich, A., Crocker, P., Kowalski, K., & DeLongis, A. (2013). Applying self-compassion in sport: An intervention with women athletes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(5), 514-524. doi:10.1123/jsep.35.5.514

Taranis, L., & Meyer, C. (2010). Perfectionism and compulsive exercise among female exercisers: High personal standards or self-criticism? Personality and Individual Differences, 49(1), 3-7. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.024

Williams, P. (2008). Vigorous exercise, fitness and incident hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Med Sci Sport Exerc, 40(6), 998-1006. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816722a9